SINGAPORE: CITY OF DESIGN, BY DESIGN - GREEN SPACES MATTER

“Singapore is ‘the canary in the coal mine’ for biophilic design. The country’s dense environment puts it at severe risk of climate change so we must innovate now - to push the boundaries of what is possible today to save our future.” - Leonard Ng, Country Director at Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl

January 24, 2022

In the aftermath of COP26, where goals were set to secure global net zero emissions and keep the global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees, countries are addressing their policies towards climate change. Singapore is already leading the way in efforts to create a greener urban environment. While the initiative to green Singapore was originally focused on giving the city state a distinct and internationally desirable image, today this approach is praised for its ability to tackle urban heat, assist with sustainable water management, and improve biodiversity in the city.

Singapore is building its reputation as a ‘City in Nature’, with the government having originally coined the vision and term ‘Garden City’ in 1967. Within Singaporean design, there has long been a strong consciousness that green spaces matter, and urban planners have woven in nature throughout the city and its buildings. Now all new developments must include plant life in some form, whether that’s green roofs, cascading vertical gardens, or verdant walls.

In February last year, the Singapore government launched its Green Plan 2030 - a whole-of-nation movement to advance Singapore’s national agenda on sustainable development. The Green Plan charts ambitious and concrete targets over the next 10 years, including a commitment to set aside 50% more land – around 200 hectares – for nature parks so that every household will live within a 10-minute walk of a park. By planting one million more trees across the island, which will absorb another 78,000 tonnes of CO2, Singapore hopes to enjoy cleaner air, and cooler shade.

According to the Centre for Liveable Cities, in 2020 almost half of Singapore’s land was covered in green space, with a tree canopy percentage of almost 30%, making Singapore one of the greenest cities in the world. Many of its citizens have made great use of parks during the pandemic lockdowns, which act as ‘green lungs’, allowing breathing and exercise space within a dense city environment. Today, leading landscape projects in Singapore are impressively multifaceted in terms of delivering ecosystem services in addition to amenity for people, and some working in the field are exploring a possible shift towards a ‘wilder’ nature in the city.

For this newsletter we share details of the landscape architecture work of design studio Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl, Singaporean government statutory board the National Parks Board (NParks) that has focused on creating the biodiverse garden-filled city that Singapore is today, as well as the research of Yun Hye Hwang of the National University of Singapore (NUS) and Thomas Schröpfer and Srilalitha Gopalakrishan of the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and the Future Cities Lab based in Singapore, who focus on exploring how to shape sustainable cities and settlement systems through science, by design. The pioneering action taking place in Singapore towards creating a more biodiverse city and nation provides a view to how other major world cities can adopt similar action over the next decade and how the work of these studios and researchers provide a blueprint for the future.

Future Cities Lab in Singapore brings transdisciplinary and distinctive European and Asian perspectives to their global mission to shape sustainable cities with the support of ETH Zurich, National University of Singapore, Nanyang Technological University Singapore, Singapore University of Technology and Design and Singapore’s National Research Foundation, under its CREATE programme.

Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl is an interdisciplinary practice with a core focus on creating liveable cities. The studio has worked on significant parks and biodiversity projects in Singapore, and their Country Director Leonard Ng provides a specialist point of view on Singaporeans’ relationship with nature. Notable projects by the studio include Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, with CH2MHill & Peter Geitz, famous for naturalising a concrete canal and a first-of-its-kind project in the country, ushering in a new ‘closeness' with nature.

The National Parks Board of Singapore (NParks) is an organisation committed to enhancing and managing the urban ecosystems of Singapore as a ‘City in Nature’. The government agency acts as the lead agency for greenery, biodiversity conservation, wildlife and animal health, welfare and management with the aim of enhancing the community's overall well-being, and the vision of creating a City in Nature. Projects include national-level initiatives like the Park Connector Network, Rail Corridor, One Million Trees Movement and Gardening with Edibles. The organisation also works closely with the community to enhance the quality of the Singaporean living environment and their ‘treesSG’ website maps and records data (including from the public) on the trees of Singapore.

Yun Hye Hwang is a landscape architect and Associate Professor in the Department of Architecture in the College of Design and Engineering at the National University of Singapore. Her research, teaching, and professional activities speculate on emerging demands in fast-growing Asian cities by exploring ecological design and management versus manicured greenery and the multifunctional role of everyday landscapes. She focuses on transferring knowledge of urban ecology from academia to practice through active interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaborations.

RAMBOLL STUDIO DREISEITL

Interdisciplinary practice Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl is a studio built on the philosophy that a vibrant public realm is at the heart of liveable cities. The studio seeks to create communities, bring people in touch with nature and use it as a source of learning, pleasure, health and wellness. They are also incredibly focused on water, whether visible or invisible, playing an essential role in the vitality of urban life.

The studio looks to solve multiple urban challenges by creating desirable green spaces often on marginal land while at the same time solving stormwater flooding problems, improving water quality and thereby creating harmonious blue-green solutions. All of this increases the resilience of urban areas. The company’s scope of work ranges from strategic framework masterplans to the applied scale of streetscapes, parks, and plazas.

Country Director Leonard Ng believes that for Singapore to overcome climate change, the whole nation needs to work together with the government. Like Prof. Thomas Schroepfer and Srilalitha Gopalakrishan from Future Cities Lab mentioned below, Ng finds that the biggest challenge is a larger public mindset change that allows for people to see how climate change mitigation efforts and greener cities will benefit them directly.

Notable projects by the studio include the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park project, in collaboration with CH2MHill and Peter Geitz. Bishan Park is one of Singapore’s most popular heartland parks. As part of a much-needed park upgrade and plans to improve the capacity of the Kallang channel along the edge of the park, works were carried out to transform the utilitarian concrete channel into a naturalised river, creating new spaces for the community to enjoy.

Ng comments: “The project was designed to maximise the catchment of water that falls naturally on the island, as well as creating a sense of ownership that will run through generations, so people will want to protect the natural environment.

The project encourages a biodiverse ecosystem – with birds and otters, among others, colonising the space because it was designed for people and nature to coexist in harmony. When people feel closer to nature and want to preserve it, this is successful biophilic design - using nature to energise and charge people and allowing them to reconnect with nature as our ancestors did.”

The project is part of the Active, Beautiful, Clean Waters (ABC Waters) Programme, a long-term initiative of Singapore’s Public Utilities Board (PUB) to transform the country’s water bodies beyond their functions of drainage and water supply, into vibrant new spaces for community bonding and recreation. The project converted a 2.7km-long straight concrete drainage channel into a sinuous, natural river 3.2km long, that meanders through the park. Sixty-two hectares of park space has been sensitively redesigned to accommodate the dynamic process of a river system, which includes fluctuating water levels, while providing maximum benefit for park users.

The park also features three playgrounds, restaurants, a new look-out point constructed using the recycled walls of the old concrete channel, and lots of open green spaces complementing the natural wonder of an ecologically restored river in the heartlands of the city. The project was the first of its kind in Singapore, bringing the idea of a new ‘closeness’ with nature.

.jpg)

Lakeside Garden by the studio (with CPG Consultants) is the first phase of developments at Jurong Lake Gardens, which is Singapore’s first national gardens in the heartlands. The project complements two existing world-class national gardens – Singapore Botanic Gardens (SBG) and Gardens by the Bay (GB). SBG’s strength lies in its botanical emphasis, research and heritage value, whilst GB’s strength is in its themed gardens and sustainability efforts. Jurong Lake Gardens’ focus is to be a people’s garden, accessible to all segments of the community.

The 53-hectare Lakeside Garden development aims to restore the landscape heritage of the swamp and forest as a canvas for recreation and community activities. The design is a conscious effort to bring back the nature that was unique to the Jurong area. The public can see a restored swamp forest and wetlands, a nature-themed play area, allotment gardens, lifestyle and sports facilities.

Ramboll Studio Dreiseitl created a meandering boardwalk that brings visitors close to the water’s edge along the western part of Jurong Lake. The Rasau walk takes visitors through a restored freshwater swamp forest that has been enhanced with some 50 species of plants. The wetland habitat is inundated with water based on the water levels in the lake, creating zones for water birds to feed and forage. Rasau Walk is connected to the adjacent Grasslands and wetland trails, where visitors can experience a variety of habitats and a wide range of fauna, such as Grey Herons, Oriental Pied Hornbills, and Smooth-coated Otters. Enhancing habitats for wildlife and keeping the tranquility of the area are key considerations in the development of Lakeside Garden, enabling visitors to enjoy nature and biodiversity.

The project also features Forest Ramble, a nature-inspired 2.3-hectare playground for children with 13 different adventure stations that encourage kids to mimic the actions and motions of the animals that inhabit the freshwater swamp habitat. At Clusia Cove, children can experience a unique water playground featuring tidal patterns, surface ripples and directional currents that mimic water movement of coastal shores. Cleansing biotopes, which serves as a natural water treatment system and UV treatment, are used to disinfect the water before it is pumped into this play area.

A one-stop community-cum-residential integrated development where WOHA Architects were architectural lead and Ramboll Studio Dreisteitl, the landscape architects and storm water management consultant, Kampung Admiralty is a flagship project that brings together a multitude of programmes under one roof. Commissioned on a tight 0.9ha site with an imposed height limit of 61m above sea level, the development helms the exploration of inter-community dynamics and urban density in land-scarce Singapore, where the increased stress on the ground level demands creative ways of intensifying land use. The project won a President*s Design Award, Singapore’s highest honour for design, in 2020.

The architectural scheme builds upon a layered ‘club sandwich’ approach comprising a vibrant, public People’s Plaza with sheltered tropical community spaces, retail and hawker centre on the ground tier, Admiralty Medical Centre spread out across two floors in the mid-tier, and a tranquil, more intimate and semi-private Community Park with the Senior Care Centre, Childcare Centre, Senior Activity Centre, Sky Terrace and Studio Apartments for seniors on the new upper ground tier.

The abundance of greenery within Kampung Admiralty serves as an ideal venue for the community to relax and bond. With tree planting strategies that comprise biodiversity, foliage and fruit trees, residents can plant edible and medicinal plants in the Community Farm and Herb Garden.

SINGAPORE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY AND DESIGN / FUTURE CITIES LAB GLOBAL

Future Cities Lab (FCL) Global is a research collaboration between ETH Zurich and four Singapore universities – National University of Singapore (NUS), Nanyang Technological University Singapore (NTU Singapore) and the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) – with support from the National Research Foundation (NRF). The centre aims to strengthen the capacity of Singapore and Switzerland to research, understand and actively respond to the challenges of global environmental sustainability.

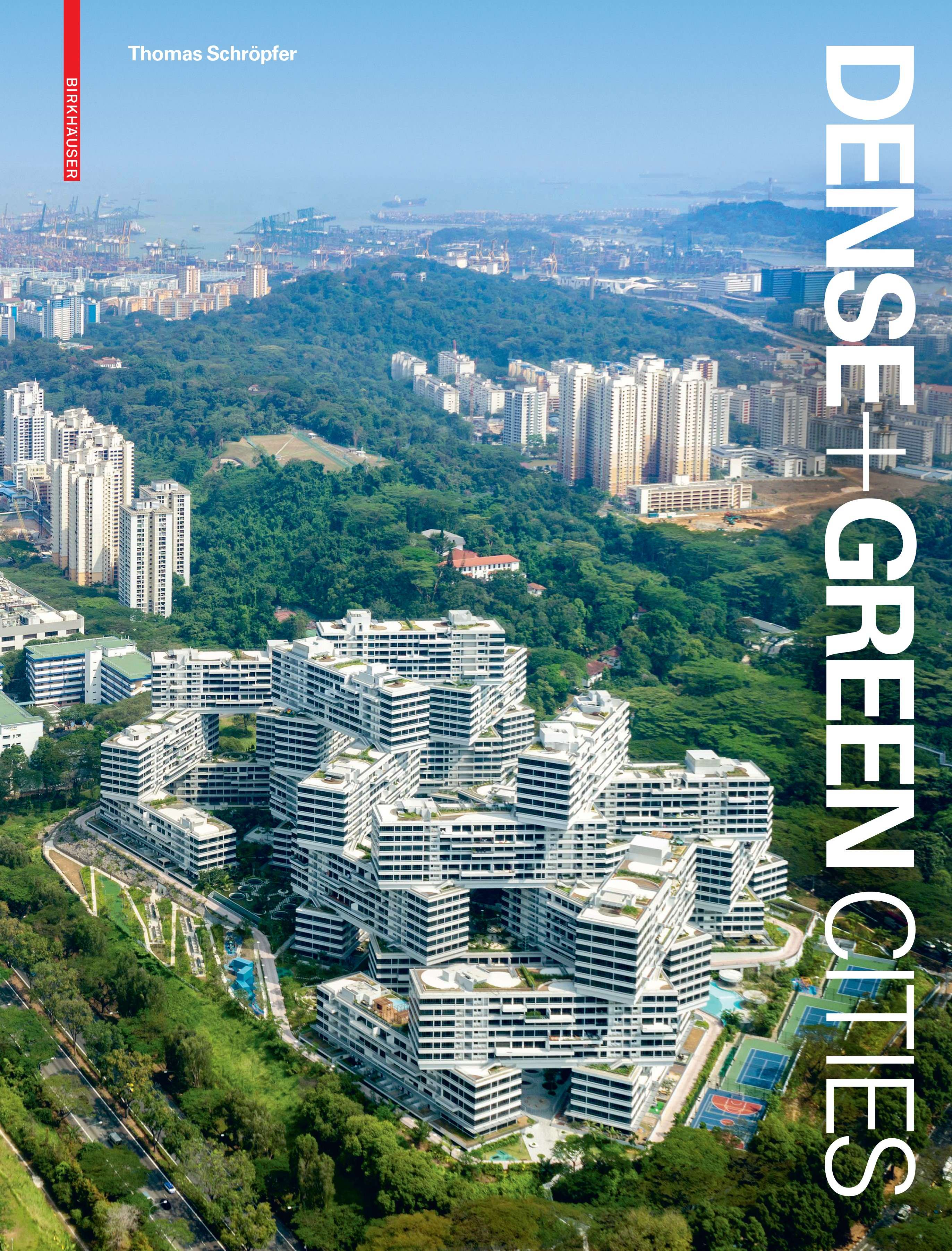

Principal Investigator at FCL, Prof. Thomas Schröpfer from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) and his colleague at FCL, landscape architect and President of SILA (the Singapore Institute of Landscape Architects) Dr. Srilalitha Gopalakrishan, are exploring ‘Dense and Green Building Typologies’. Schröpfer’s recently published book titled Dense+Green Cities: Architecture as Urban Ecosystem (to which Gopalakrishnan contributed as a researcher) looks at new building typologies that are emerging in the Singaporean context in particular, as well as internationally, and companies that are experimenting with landscape and architecture in high-density contexts.

Schröpfer comments: “Singapore has been a very interesting case study to look at as it is very dense and there is an extreme pressure on development. As it grows, the only way the city can go is up - to become a vertical city.

Over the last 10 years the government has introduced new policies that incentivise green architecture and there are many interesting cases in the context of Singapore – within buildings, as well in the urban design strategies that architects deploy.”

Gopalakrishan and Schröpfer believe there is a social dimension to green city spaces, and as part of their studies they are exploring how much people like green spaces, how often they use sky/roof gardens, and the ways these high green spaces substitute those on ground level. Their research also looks into the environmental performance of green buildings – how they improve the urban climate, assist with the issues of overheating through cooling, and measuring the positive impact on biodiversity. Today, Gopalakrishan and Schröpfer are scaling this research up, looking at how the impact of these buildings is bigger in larger urban systems.

Schröpfer comments: “These buildings cost 3-5% more than regular buildings, and the same additional cost for maintenance and upkeep. However, despite this, the ROI is high as people are willing to pay more money to live and work in these buildings, or even simply to have a view of one of them - a great example being in New York, where real estate around the famous High Line has exploded.”

As president of SILA, Gopalakrishan works at multiple levels – from strategy to grass roots, to educating the public at large about what having a green city entails. As a landscape architect, she has seen how the profession has changed and transformed dynamically in Singapore:

“Singapore’s vertical green landscape has added much dimension to what vertical green cities can look like. Landscaping in its complete sense is a lot more than just aesthetics. The transformation of Singapore has been very exciting – despite there still being a long way to go. Singapore is now pushing the bar even higher toward a ‘city in nature’, which is a very different approach to how cities should be in future. Singapore is showing cities globally how it can be done. Creating this type of urban environment is not just about adding plants here and there, but how you plug yourself into the larger urban system. Singapore is taking big strides ahead.”

Gopalakrishan and Schröpfer have found that the main challenge in achieving a ‘city in nature’ is public acceptance that humans need to coexist with other living beings.

Gopalakrishan comments: “It is also about how you transfer biophobia to biophilia, which is one large step. People want ‘butterflies but not bees, birds but not worms’, and gaining acceptance that it is a larger system and network is challenging. People need to look at landscapes as part of this bigger ecosystem, and when they are willing to accept this [green cities] will succeed.”

The work at the FCL has found that there are many different touch points for helping foster acceptance – for example through education of the general public (who will then speak this same language to their children). Their findings have found that the ‘coexistence’ element brings up a lot of design questions for practitioners to work with over the next 10 years.

https://sec.ethz.ch/research/fcl.html

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE

Yun Hye Hwang is an accredited landscape architect in Singapore and Associate Professor of Landscape Architecture at the School of Design and Environment at the National University of Singapore. Through her role at NUS, she explores how to connect quantifiable and qualifiable academic findings and practical applications of urban greening, and her papers are about design strategies that can be implemented in real world situations. Hwang firmly believes that green spaces are vital to building quality of life.

Hwang comments: “Biophilia is about an attitude to nature – we can use it as a framework for moving landscape design and planning concepts. It is about the relationship between human and nature. Our programme (Bachelor and Master of Landscape Architecture program, Department of Architecture, College of Design and Engineering, National University of Singapore) is to make this more visible and show functional benefits to laypeople so they appreciate these things.”

She has seen significant changes over the past 10 years in how design approaches and management of landscapes and gardens in Singapore have been evolving, co-led by national policy, and design disciplines.

Hwang comments: “A couple of decades ago, major projects were done by foreign/overseas landscape firms, though now more local or/and naturalized landscape architects who have been trained/practiced in Singapore are leading/having the opportunity to shape their own visions for the country.”

Education on the subject in Singapore is growing and in 2020, the Bachelor of Landscape Architecture BLA (in addition to the existing Master degree programme MLA) in Landscape Architecture opened at NUS, with the mission to nurture the next generation who are well equipped to create and care for our landscapes in the face of the most pressing socioecological issues of our time in this region. Hwang’s approach, bridging research, practice at her Urban Wild Lab at NUS develops the actionable design and management strategies towards socio-ecological resilience for fast-growing Asian cities where rapid urbanisation is accompanied by many human-caused environmental issues. While common practices of landscape planning and design have typically paid less attention to natural successions and changes in post-construction, the lab makes a unique contribution by addressing these research lacunae that are pre-emptive and provocative in theory, at the same time feasible and applicable in practice, to generate socio-ecological value of urban landscapes in the long run. Her work looks at how we can benefit and learn from natural ecosystems; and how to make such systems appealing to everyone.

In her practice, Hwang worked on the international award-winning, Ventus Naturalised Garden together with NUS Facility Management Team (OFM), as well as the Courtyard Forest Garden at the NUS.

The Ventus Naturalised Garden on the main campus of NUS is a prime showcase of an alternative landscape typology that allows spontaneous plants to overgrow the existing monotonous campus lawn with minimum design interventions. The Garden provides a connection between a woodland park and a secondary forest. This is a rare type of landscape to find in Singapore, where the majority of urban greenery has been highly tamed with intensive maintenance regimes. The project demonstrates that even a small piece of land can accommodate a variety of flora and fauna, while serving as part of an ecological network at the city scale.

Courtyard Forest Garden at the NUS School of Design and Environment was designed in collaboration with DP Green. Here, the team used native primary forest species, with a view to the garden undergoing natural succession over time to generate a more biologically diverse condition on the site. Hwang believes the most important and unique opportunity for landscape architecture in Singapore and other tropical cities is the potential to work with tropicality (hot and humid, stable weather conditions) and time – fast-growing vegetation, with an appropriate level of maintenance, which can allow for gardens that change and evolve. Typical landscape projects have a tendency to keep gardens and landscapes perpetually the same, but Hwang believes things can grow and evolve over time to more than what the original concepts were – if developers and clients allow them to.

She comments: “I see biodiversity as an essential indicator of the value of biophilic design. It is required to address the global biodiversity emergency.”

“Singapore’s green policy advances the prototype for biophillic design. The next step for the city is to view itself as a heterogeneous and dynamic ecosystem, with careful planning to work out quantities of quality green spaces to create more balanced, evolving, natural environments in the city.”

NATIONAL PARKS BOARD (NPARKS)

“Today, Singapore is one of the greenest cities in the world. The lush urban greenery that we have is a result of sustained and dedicated efforts to green up Singapore over the past few decades.” - Damian Tang, Senior Director/Design, National Parks Board.

Singapore’s modern greening journey began with the first nationwide tree planting campaign in 1963. In 1971, the first annual Tree Planting Day was launched and with that, greening has become an integral part of Singapore's DNA. With the vision of creating a City in a Garden and enhancing the community's overall wellbeing, the National Parks Board of Singapore (NParks) has spent several decades ‘greening’ Singapore’s roads and infrastructure, transforming the country’s parks and gardens into spaces for everyone to enjoy, and gazetting areas of core biodiversity to conserve Singapore’s native biodiversity. Singapore is now transforming into a City in Nature, where a biophilic design approach is important in restoring habitats and the community is engaged in sustaining the national greening efforts.

Today, NParks manages more than 350 parks across the country, 3,347 hectares of nature reserves, the Singapore Botanic Gardens, Jurong Lake Gardens, Pulau Ubin and the Sisters' Islands Marine Park. The organisation also oversees Singapore’s extensive network of Nature Ways (routes planted with specific trees and shrubs to facilitate the movement of animals like birds and butterflies between two green spaces), and the over-300km-long Park Connector Network that links major parks, nature areas and residential estates island-wide. They also run over 3,500 educational programmes across their various green spaces. Community in Bloom, Community in Nature and Gardening with Edibles are key in enabling the community a closer experience of nature and in promoting mental wellbeing.

With challenges like extreme weather patterns induced by climate change and increasing urbanisation, there is a need to build a more liveable, sustainable, and climate-resilient Singapore for present and future generations. Tang shares that the City in Nature vision is the country’s next bound of urban planning – to create a green, liveable, and sustainable home for Singaporeans.

“At NParks, we have five key strategies to transform Singapore into a City in Nature: (1) conserving and extending Singapore’s natural capital; (2) intensifying nature in gardens and parks; (3) restoring nature into the urban landscape; (4) strengthening connectivity between Singapore’s green spaces; (5) developing excellence in veterinary care, animal and wildlife management. As can be seen from the strategies, we are strongly focussed on conserving our natural heritage, while expanding greenery and creating a more naturalistic landscape in the city. In doing so, we provide more recreational opportunities for people while protecting our core biodiversity areas. Naturalising canals and using other nature-based solutions will help build resilience against sea-level rise and inland flooding while supporting rich biodiversity. And the community is a key partner in these efforts. It is only with their support that we can sustain our greening efforts.” – Damian Tang, Senior Director/Design, National Parks Board.

Launched in May 2005, Community in Bloom is a nationwide gardening movement by the organisation that aims to foster a community spirit and bring together residents - both young and old - to make Singapore a City in Nature. It now has over 1,700 community gardens across Singapore that have engaged more than 43,000 gardening enthusiasts. The Gardening with Edibles initiative was launched in June 2020 to encourage the Singaporean public to garden at home with edible plants. Under the programme, NParks distributed free seed packets to interested members of the public and published gardening resources on its website. The initiative is also aligned with Singapore’s national strategy to strengthen its food resilience as a nation. The initiative is working with the “30 by 30” goal led by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA), which aims to produce 30% of Singapore’s nutritional needs locally by the year 2030.

Beyond gardening, the public can get up close and personal with nature and greenery at seven therapeutic gardens in parks across the country. NParks targets to have 30 therapeutic gardens by 2030 as part of the City in Nature journey, with the goal to enable more Singaporeans to benefit from the positive effects of nature on their health and wellbeing. NParks believes community is key to the success of greening efforts, and hosts nursery tutorials, webinars, and virtual park tours in the effort to raise awareness and help the population play an active role in the greening of Singapore.

The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the value of greenery in a densely populated city like Singapore. NParks has observed more Singaporeans visiting parks and nature reserves or taking up gardening as a hobby during the pandemic. NParks recently conducted a study on the effects of gardening on people’s mental resilience during the pandemic. Conducted in collaboration with the Mind Science Centre of the National University Health System, the study compared the mental resilience of a general community with participants from the Gardening with Edibles initiative. The study found that the group who engaged in weekly gardening had higher mental resilience than those in the general community and this trend was consistent across different age groups.

For Tang, the role of design is to support the ideas and initiatives that residents have for the vision of their city. Zoning a plot of land as green space – designating it as parkland or retaining vegetation – is only the first step.

He says, “The city level of design planning requires the simultaneous design of the blue and green system on a macro to micro level. Design integrates and further connects the living network layers of flora and fauna with the urban infrastructure and architecture of the city. This process also includes how individuals and communities use the spaces; how they interact with and be engaged with them.”

An example Tang shared is the NParks Friends of the Parks programme – a ground-led initiative to promote community stewardship and responsible use of Singapore's parks. The initiative consists of localised communities comprising of stakeholders such as residents, business owners, and volunteers to encourage active and responsible uses of our parks through ground-led programmes and initiatives. These ‘Friends communities’ are also involved in planning and designing upcoming green spaces so that these spaces cater to their needs and aspirations.

Tang remarks: “Urban green planning needs to address the challenges arising from climate change and the disruptions to people’s lives. There is a need to understand the impacts of climate change on natural and human systems and develop strategies for nature-based solutions into our green planning to safeguard and future-proof Singapore against environmental challenges. The way forward is to weave creativity into the planning process to help rethink the way cities are planned and to look beyond boundaries to work together through the complex issues of designing and planning for a climate-resilient nation. At the same time, we also need to leave sufficient space and options for future generations to design and plan for their needs and aspirations as well.

Green urban planning that cuts across agency boundaries and integrates the hardscape and softscape will make cities like Singapore more liveable and climate resilient. These elements will also encourage more community stewardship of our urban green spaces that Singaporeans are proud to call home.”

https://www.nparks.gov.sg/treessg

PRESS ENQUIRIES AND IMAGES:

Camron PR: designsingapore@camronpr.com